Magical Thinking

Grief on the Autism Spectrum

Linda Cobourn picked up a pencil when she was nine and hasn’t stopped writing since, but she never expected to write about adult autism and grief. When her husband died after a long illness, she began a remarkable journey of faith with her son, an adult with Asperger’s syndrome. The author of Tap Dancing in Church, Crazy: A Diary, and Scenes from a Quirky Life, she holds an MEd in Reading and an EdD in Literacy. Dr. Cobourn also writes for Aspirations, a newsletter for parents of autistic offspring. Her current work in progress chronicles her son’s unique grief journey. She can be contacted on her blog, Quirky, and her Amazon author page.

Allen sat next to his father’s hospital bed, concentrating on the ice cube melting in each palm as he tried to block out sensory overload—the voices of the paramedics in the next room, the sounds of his siblings crying on the back deck, the whirling red lights of the ambulance waiting outside, his mother’s voice murmuring to the doctor.

Everyone told him his father was dead. But Allen just couldn’t let himself believe .

This was the scene at my house on the evening of July 13, 2019, when my husband, Ron, passed quietly away at home after a long illness. While each of my three children needed to find a way to grieve the passing of their father, it was Allen—an adult on the autism spectrum—who had the most difficulty.

Allen attended his father’s funeral. He had seen Ron’s body in the coffin and was present when it was lowered into the grave at Lawncroft. None of those facts changed Allen’s belief that with the proper combination of words and actions, his father could return.

Six days after Ron’s death, Allen and I were alone in the house for the first time. I sat in my rocking chair, sorting through bills I could not pay, and heard Allen in his bedroom upstairs, stomping his feet and banging furniture. I closed my eyes and took deep breaths, reminding myself how difficult it was for Allen, who saw the world in concrete terms, to accept the finality of his father’s death. He thundered down the steps, shouting.

“They’ve taken it! They’ve taken it! They came and took Dad away and won’t bring him back and now they’ve taken away the measuring tape that Dad gave me! I hate those people from the ambulance! I HATE THEM!” His grief echoed in the hallway, wrapping him in sorrow. He collapsed in a heap at the bottom of the steps, and his sobs pierced me.

My own grief was raw and open. How could I hope to help my son accept Ron’s sudden death when I was still trying to pick up the pieces of my own shattered heart?

His journey towards acceptance began with the trees.

Two weeks after his father died, Allen came in from the yard and told me, “The trees are whispering Dad’s name.”

“Oh,” I said, thinking the wind was hardly blowing that day. “Are you sure?”

He nodded solemnly. “Not only that, Mom, they’re saying that Dad isn’t going to stay dead. They’re saying that Dad is going to find a way to come back to us! Isn’t that good news?”

I’m pretty sure I nodded while I wondered if I should call for emergency services or at least dial the number of Allen’s therapist. Instead, I began a quest to help my son, with his atypical brain, to process Ron’s death in a healthy manner.

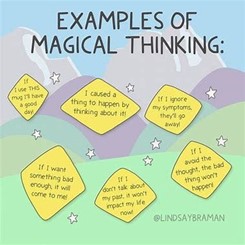

I discovered that people on the spectrum, and even some of us with typical brain function, use “magical thinking” to avoid the immediate pain of a loved one’s death. According to St. James, Handelman, and Taylor (2011), magical thinking provides a connection to what has been broken and helps the thinker cope with cultural expectations of control.

During the days between Ron’s death and funeral, Allen needed to hold himself together, shake hands, accept hugs, and say “thank you” to those who expressed their condolences. As the researchers at Indiana University note (2014), “normal can be exhausting.”

My research unearthed many helpful tips about grief for people on the autism spectrum:

- Autism grief is not neurotypical grief (Fisher, 2014)

- All reactions to grief should be seen as valid. Disregard no idea that helps (Indiana University, 2014)

- Find a way to share the sorrow (Mental Health America)

Even so, Allen’s insistence that “Dad’s not dead” continued to occupy his mind, and meltdowns occurred almost daily. I searched for literature to help me understand Allen’s reactions and offer him some comfort. Karla Fisher’s excellent insights into her own grief process as an autistic adult helped me make sense of Allen’s episodes and sensory processing failures (Thirty Days of Autism). An article in Psychology Today stated that “the death of a parent in the home—where safety and security are assumed—can easily throw someone on the spectrum into a meltdown” (Soraya, 2014). Ron had died at home, sitting in his easy chair, a baseball game on the television. What could be more stressful than having your father die while you were home alone with him?

Frantic to help my son, I used my journal to scribble down and attempt to sort out Allen’s unique ideas:

- The trees say Dad is alive

- The squirrels can carry a message to Dad

- Dad needs really fast skates so he can escape death

- Dad needs a new body because his old one is worn out

- We need to do something that will bring Dad back again.

Eventually, I returned to the research on “magical thinking” and decided this would be a useful tool for helping me understand and help Allen. A few days later Allen told me, “We need to find a really tall tree. I’m going to send a message up the tree to the squirrels and they’ll find Dad.”

At that moment, as I looked into the hope that filled my son’s eyes, I made a decision: I would “disregard no idea that helps” and “find a way to share the sorrow.” I would join Allen on his magical journey to find his father.

I took a deep breath and whispered a prayer. “I know where there’s a really tall tree.”

Our journey began.